My personal search for The Truth About Spruce has been ongoing for many years, but took a turn when someone insisted that Picea abies and Picea excelsa were two names for the same species. I had always understood they were separate, as the woods associated with the two names were certainly (I thought) quite different. I got busy with the web, some books and spoke at length with a couple of experts. I gained a better idea of what's what now with European spruce, and here's what I found out. First of all, the guy

who lumped them together was right and I was out

of date. In terms of the lutherie world, or for that

matter the world of plant biology, there is but one

species of spruce—used for lutherie—in all of

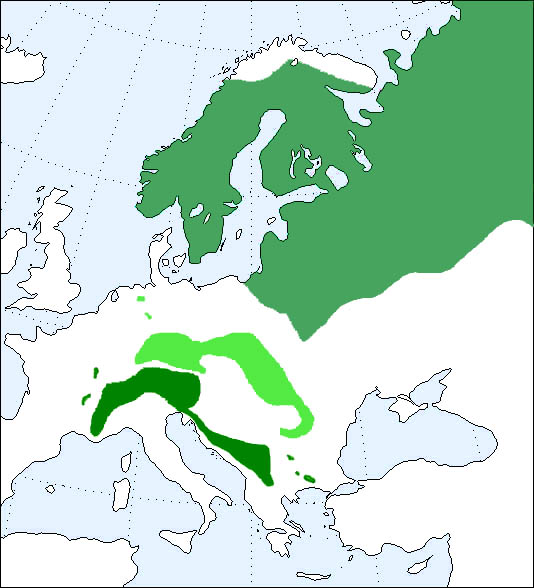

Europe: Picea abies. The map below shows the

three current European ranges of Picea abies,

a tree commonly known as Norway spruce in the US and Canada,

epicéa commun

in France, épinette de Norvège in Québec,

gemeinefichte

or rotefichte in German, and jel europeiskaya in

Russia. Other common

names abound, and the overriding one, in many

languages, is the translated local

equivalent of red spruce. Here is one reason it's known as red spruce:  Here's a map of the range of Picea abies:

As with most spruces, these trees naturally and historically live in cooler, higher elevations, preferring lots of moisture and rich, somewhat acidic soils. The original range includes most of Europe outside permafrost from the Scandinavian arctic down to northern Greece, west to the French Massif Central. The northern range extends off the map towards the Urals where it meets and hybridizes with Picea obovata. P. abies has been planted all over the planet by now, and adapts to a wide variety of soils and climates probably because it survived the Ice Age. The largest known example of one is in a park just west of Moscow, though this is an anomaly, since these trees typically don't live longer than about 200 years. Tiny remnants of the pre-glacier and pre-human-impact older range are found in the Pyrenees, down the center of Italy, and along the south coast of the Black Sea, in northern Turkey. The most southerly of the three ranges in this map (darkest green) lies in France, Switzerland, Italy and a bit of Austria and Slovenia - in other words, the south face of the Alps - trailing down through the mountainous parts of Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, with remnants in Bulgaria and the Balkans. This is the part of the historical range that escaped glaciation and provided the reservoir for the reintroduction of the species back into the northern ranges after the glaciers retreated. The spruces of the lower range were, until recently, taxonomically classified as Picea excelsa. Many sources still refer to that as a species, while some refer to it as the German botanical designation for Picea abies. In any case, Picea excelsa has now been folded together with Picea abies as a single species. If you see the term Picea excelsa, it'll be in—or referenced to—older literature. The trees in the lower range are also still classified by some botanists as a subspecies called Picea abies v.excelsa. It is debatable if this is a wise designation, as the only thing distinguishing this so-called subspecies is how it grows in that environment. A propos, this is the range from which the Cremonese master violinmakers and the lutherie elite of Europe has historically gotten their wood. The white band separating the two lower ranges in the map above marks the high elevations of the Alps where icebergs try to grow, while the larger blank area east of there is the lowlands of Hungary and so on. The middle light-green range on the north slope of the Alps and across southern Germany and east into Poland and Czechoslovakia contains Picea abies, most of which has been reintroduced since 1800. Because of the thorough exploitation and devastation of the forests through the end of the 18th century and the enormous timber demand in early industrial times, the natural forests, which had already regrown after the retreat of the glaciers, were eliminated and eventually reborn as artificial forests. Ironically, the seed stock for the reintroduced Picea abies came from the relatively unscathed Scandinavian range (gray-green) at the top of the map, which had re-established itself from that southern reservoir after the last Ice Age.

It is an irony that over the last

fifty years or so, forest

management in Germany has increased forest size

considerably (in stark

contrast to the rest of the world) but its air

pollution is so extreme

(largely blowing in from other countries) that the

forests are very unhealthy

and the yield from that acreage is decreasing. Picea

abies is acutely vulnerable

to the pollution problems, notably acid rain. These

photos are from the Alps in Bavaria:

More information about acid rain here. Moreover, if you have

ever spent time talking wood with instrument makers

in Germany, they will chuckle and tell you they

consider "German spruce"

not just a misnomer but an unlikelihood. They

generally get their spruce

from farther south, in Italy, Slovenia, Switzerland

or France. This has

always been the source of the best lutherie spruce.

As Horst Grünert,

a bass and cello maker in Penzberg, Bavaria, once

cheerfully told me, he'd

go right out with his chainsaw and get the rare

spruce in Germany if he could

find it, but he said that for all intents and

purposes, it had been extinct

in Germany for several centuries (again, see below).

The spruce I was seeing

all over the Alps was, he said, good for fence posts

and pulp, and that's

what it was farmed for. Outside of parks and so on,

I never saw trees larger

than about eight inches either. That's them in the

above three photos. I know of only one wood cutter

inside the German border, high in the Alps close to Switzerland, who

harvests and mills spruce for lutherie. In conclusion, believe this:

Sidebar: Intercontinental trade in forest seed was established in the early 1700s, when seed of several eastern American species (yellow locust being a big one) were frequently shipped to Europe, mainly for use in ornamental plantations. Regular forest plantations of Picea glauca (white spruce), Pinus strobus (eastern white pine), and a few other American conifers, however, also began to be cultivated in Europe shortly after 1700. The first seed samples of northwestern American species, including Douglas fir and Sitka spruce, were sent to Europe about 1825 by the famous botanical explorer, David Douglas. Trade on a substantial scale in these species, however, did not begin until after the opening of the Pacific Railroad in 1869. The center of the trade in those days was San Francisco, where seed from the northwest was shipped by boat and thence east by train to dealers on the Atlantic coast, or direct to customers in Europe. Darmstadt in Germany was the other end of the pipeline in this trade. Bearing in mind that Picea

glauca was introduced into Europe about 1700

from America and mainly used in shelterbelt

plantings, it may be mentioned,

merely as a curious fact, that seed of this species

has been exported in

considerable quantities from Europe (Denmark) to

Canada during the last

decades. Even seed of such American species as Sitka

spruce and western

red cedar (both, however, of selected origin) have

recently been exported

from Denmark to American dealers. This is indeed an

improved forest seed

version of "carrying coals to Newcastle."

Unless you cut the tree

yourself or can be absolutely certain where

that tree was harvested, it is probably safest to

just call it spruce.

If you're certain it grew and was harvested in

Europe, there's no point

in getting your turban in a twist over common names.

If someone says

German spruce, just think, "OK, Picea abies,

or European

spruce."  I think to discern any differences between, say, Italian and Swedish and French spruce, you need only look to some analogs in the local (North American) spruces, because so many examples lie before us, a record that is huge and fresh. Just consider the staggering output of the big guitarmaking concerns like Martin, Gibson, and Taylor, not to mention folks like SCGC, Bourgeois, Collings and so on. What a consistent and generous resource for the rest of us, just to examine and evaluate their results. For starters, many thousands of guitars by these major makers are made from Sitka that grew in British Columbia, or Oregon, or other places. Can anyone tell them apart? By the same token, is Engelmann from New Mexico reliably discernible from Engelmann from Canada? Can anyone tell them apart after they've been made into guitars? Continuing in guitar-brain,

here’s another angle. Since the enormous output

centers largely on a

few basic models (dreadnought, OM, etc.), we can

safely consider and compare

a very large number of guitars made of different

species of spruce. Is

any one of them distinct tonally? No, not really.

We all know that some

guitars made from [ x ] species are terrific, some

are blah, regardless

of age or species. Can anyone tell them apart

visually? Of course not, it's simply not possible.

Any spruce

is capable of looking exactly like any other,

because spruce, being wood after all, is not a homogeneous

substance at all. Picea abies from

Jugoslavia is usually identical in appearance

to Picea rubens from the Adirondacks and Picea

engelmannii from northern

Idaho. Even Sitka, which some folks fervently

believe is very distinguishable,

can mimic other species, and conversely, the dark

lines that supposed to

be so telltale in Sitka show up in lots of Alpine

spruce too. The only

way to be certain of a spruce species is one of the following: 1) key the living tree and harvest it yourself 2) have a trained

scientist with a high powered microscope, a

library

of appropriate reference samples and a lot of skill

and experience, give

it a serious lab analysis. And realize that there's

even some question

about the absolute reliability of this method—the

best there

is—because the reference sample libraries are not

always complete and

comprehensive. Other than that you are operating on pure faith in the seller, or on pure imagination, because things are quite often not what they seem. Back to my earlier point, and about provenance: Engelmann comes from British Columbia and it also comes from New Mexico. That's as big a geographic spread as Sweden and Italy. Sitka comes from Alaska and from northern California—same thing. Adirondack comes from Georgia and from Québec—same thing. Is there any reliable coherence within species? Don't bet on it. We know them all, we see many examples of their applications, and that experience, we fervently hope, informs us. But not based on a handful of anecdotes. And that's following the notion that location means anything definitive I'm really not sure it does, except in a general sense. There's good and bad spruce from any location, any species. We all know this. Species and/or location is interesting chatter, but can be a waste of time too. Being able to listen to and hear a

promising piece of wood, and knowing how to bring

out its potential, is what it is really all

about.

|

Today,

Picea abies comprises 35% of the tree cover

in Germany, and most of that

is in managed forests. Among the other major

conifers in German forests

are Picea glauca, an American import, and

Douglas fir, another American

import. These trees have been grown successfully in Germany for a

very long time (see

below).

Today,

Picea abies comprises 35% of the tree cover

in Germany, and most of that

is in managed forests. Among the other major

conifers in German forests

are Picea glauca, an American import, and

Douglas fir, another American

import. These trees have been grown successfully in Germany for a

very long time (see

below).